Surrounded by its past of art and music, Lucca is not known for its contribution to scientific culture but, in the shadow of the Walls, in some small museumsyou can find unique stories ang great wonder. The nineteenth century has left us the main "places of science" of Lucca: The Botanical Garden, the Cabinet of Natural History and the Museum of internal combustion engine.

At the beginning of the 19th century, the princess of Lucca and Piombino, Elisa Bonaparte Baciocchi,

granted the foundation of a Botanical Garden and the funds necessary to maintain it, but it was Maria Luisa di Borbone, after the fall of the Napoleonic Empire a few years later, who gave to the Royal Lyceum the plot of land of about two hectares to create the Garden.

Seeds and plants arrived from the Royal Villa of Marlia where they had arrived directly from the French collections, from the Botanical Gardens nearby noble trees such as the Cedar of Lebanon, the patriarch of the garden, planted in 1822.

Cesare Bicchi, who looked after the Botanical Garden of Lucca at the end of the 19th century,

is responsible for much of its present appearance: the formation of the most conspicuous part of the herbarium and the botanical school an important collection, of more than 450 medicinal plants, cinchona, erythrea incense, gallic pink turmeric, gentian and many others among the most used in the various countries of the world.

The arboretum in which to walk among redwoods, badgers, wollemie, beeches and other 200 different species of trees from all over the world.

The small lake dominated by the bald cypress and the legend of the beautiful Lucida Mansi who died drowning in its waters, to which were later added the little mountain with the typical species of the Mediterranean maquis and a rich collection of edible "erbi", traditional of the local cuisine.

The collection of camellias and rhododendrons that in that period embellished the parks of the villas of the aristocracy.

The heated greenhouses for the inevitable botanical wonders, exotic plants and flowers that in that period circulated abundantly from all over the world changing the habits of Europeans. Coffee, tea and chocolate could not be missing from the aristocratic tables and botanical gardens of every place in Europe.

In the Botanical Garden there are also the two multisensory paths of the trees and the botanical school dedicated to blind and visually impaired visitors and for those who want to deepen their sensitivity through touch, taste, smell, hearing.

Minerals, fossils and shells, insects and birds... mummies and Egyptian finds and the atmosphere of a Wunderkammer

(from the German 'chamber of wonders', an ancient exhibition modality inspired by eclecticism and taste for the wonderful) of the early nineteenth century at the Cabinet of Natural History that keeps alive the city's tradition for scientific studies that had great impetus with the Granducato di Toscana.

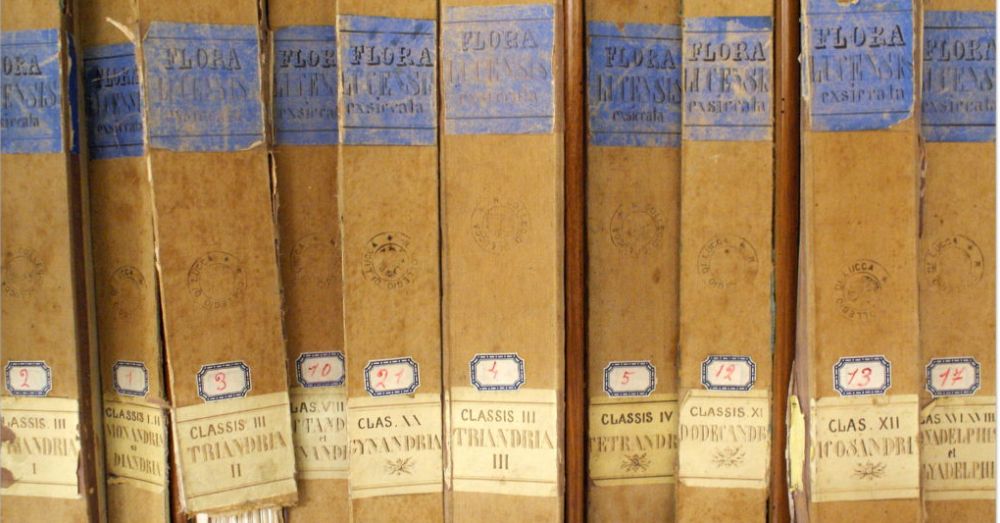

In the frescoed rooms of Palazzo Lucchesini, there is a museum within the museum with "vintage" displays

that have maintained the original layout of the original finds and subsequent donations including that of the Lucca explorer Carlo Piaggia, protagonist of important geographical and ethnographic discoveries and the Mezzetti herbarium, donated to the Cabinet by the author. About twenty dense volumes of notes on over 1500 specimens of plants mainly from the nineteenth-century Lucca territory, some of which are now extinct.

The charm and amazement of the past are also the subject of the museum, the curiosity of discoveries in the display cases objects with the strangest names: rare shells from all over the world, the largest collection of stuffed birds in Italy (3000 specimens) from the robin to the black stork, the fossil of a fish ten meters long, dioramas representing the metamorphosis of the silkworm (Bombyx mori), and even a tortoiseshell!

Also nineteenth-century the Museum of the Combustion Engine,

housed in the premises of the fourteenth-century loggias of the Guinigi.

An exhibition dedicated to the works and life of the two scientists from Lucca who invented the revolutionary engine. The only one in the world that reconstructs with punctuality the studies and progress of Barsanti and Matteucci: from life stories to the acknowledgements collected at the time for their ingenuity, to the documents that Barsati brought with him to Paris, patents, drawings, and how much could help him to claim, unfortunately in vain, the paternity of the invention.

At the centre of the exhibition , scale reproductions of the four models of engines,

running on compressed air, designed by the two scientists from Lucca to a summary of the documents that tell the birth and evolution of their studies, between December 1851, the date of their first meeting, and March 25, 1864, the day on which the Bauer engine was put into operation at the headquarters of the John Cockeril Company in Seraing near Liège in Belgium.